Everything decays–a truth that encompasses pretty much all material things. However, we as a species have been really good at protecting things that we assign value to. High-end paintings are one example of this. As we know, most paintings done in the Renaissance era were done with fresco and oil. Those mediums are known to be rather stable and do not easily fade compared to modern plastic-based acrylics. However, the Greats did have one enemy that would interfere with the immortality of their works: the environment.

Oil paints are delicate in nature. It is very easy for it to begin warping under heat and humidity, and the colors eventually fade. This is why artists sometimes “restore” works done by their formers. One famous example can be seen below of the fresco work Ecce Homo before and after a restoration attempt due to noticeable peeling paint. Incredibly, the restorer Cecilia Giménez may have become more popular than original artist Elías García Martínez for her visually appalling rendition. With that being said, conservators of art have a very important duty of maintaining the legacy of one’s work and must be treated (most of the time) with effort and care.

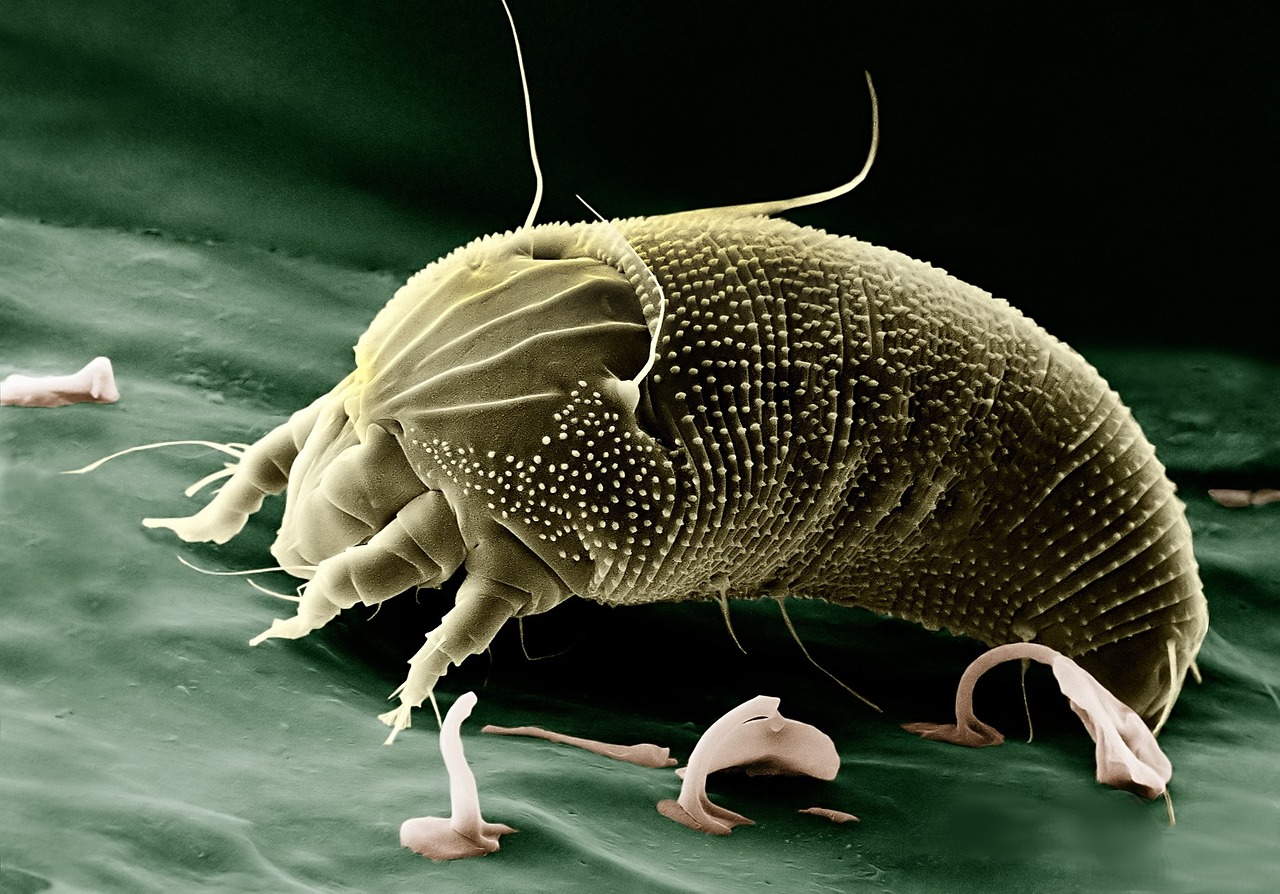

Thus, there have been developed numerous conservational tools to help identify especially stained areas or to noninvasively detect features of the artwork. For example, aqueous-based cleaning solutions may cause smearing or weaken the paint itself. To remedy this, the water’s pH or conductivity can be altered. Sometimes, tears and distortions can appear which require a re-threading of canvas. In those cases, conservators may use stereo-binocular microscopes to assist with microscopic details.

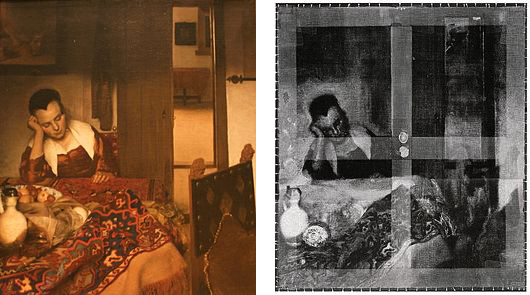

My absolute favorite tool when it comes to art conservation is X-radiography. Because the material of the canvas is less dense in respect to its paint layers, we can use X-rays to image the artwork in its entire “skeleton” structure, seeing modified layers and brushstrokes that do not make it to the official front of the painting. Sometimes, this technology can reveal hidden information about the canvas/primers used or even completely different paintings underneath that provide insight to an shifts in an artist’s ideas throughout a piece. The Art Institute of Chicago has a really cool page with an interactive feature that demonstrates just that with some paintings from the 1900s.

Overall, art conservation is a really cool field that dives into a lot more than what I mentioned in this blog. And as it turns out, a large portion of it has to do with technologies and science (which is especially nice for me because I get to write about it and share it here!). So, the next time you walk into a museum and you see a really interesting painting, think also about what lies underneath it and the process that the artist took to get to the final piece.

References

Cartwright, M. (2020, October 20). Colour & Technique in Renaissance Painting. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1628/colour–technique-in-renaissance-painting/

Ebert, B. (n.d.). Painting conservation techniques. Asiarta.org. https://asiarta.org/introduction-to-conservation/oil-paintings/painting-conservation-techniques/

Grotesque Irreverence: The Transformation of “Ecce Homo” | SEQUITUR. we follow art. (n.d.). Www.bu.edu. https://www.bu.edu/sequitur/2016/04/29/handler-ecce/

Langley, A., & Muir, K. (2021). X-Rays: Peering over the Artist’s Shoulder. Www.artic.edu. https://www.artic.edu/articles/949/x-rays-peering-over-the-artist-s-shoulder

Lizun, D. (n.d.). Fine Art Conservation. X-radiography. Fineartconservation.ie. Retrieved April 14, 2024, from https://fineartconservation.ie/x-radiography-4-4-45.html#:~:text=Thus%20when%20reading%20an%20X