The Miracle of Sight

There is zero doubt that Leonardo da Vinci was the paragon of achievement. By the end of his 67 year-long life during the peak of the Renaissance, his name was well recognized from Milan to France. In his life, he accomplished what many could have only wished to with several lifetimes. It is very hard not to understate his accolades and contributions for humanity, and a biography of his life would be impossible to contain in a blog such as this.

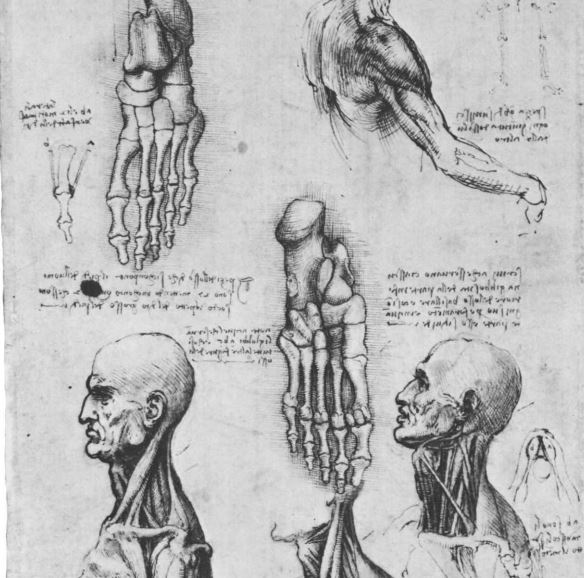

Da Vinci was known for many things, but one particular detail I believe to be especially relevant was his idea of the intersection between art and science. To him, the two were complementary—one could not exist without the other. His notebooks were multi-disciplined and were complete with illustrations and studies generated from his vast accumulated knowledge. He emphasized human sight as the most important sense to greater scientific understanding. His shocking accuracy in body systems, works of engineering, and aerial maps were a result of his unique problem solving process that he called sapere vedere (knowing how to see). More specifically, he was able to visualize the underlying mechanics and structures by learning how to dissect the harmony of different shapes and relevant visual cues in objects. Yet, Da Vinci’s drawings were not inherently complicated as he believed simplicity would provide a greater clarity to his intentions.

A Pre-Modern Modern Grasp of Anatomy

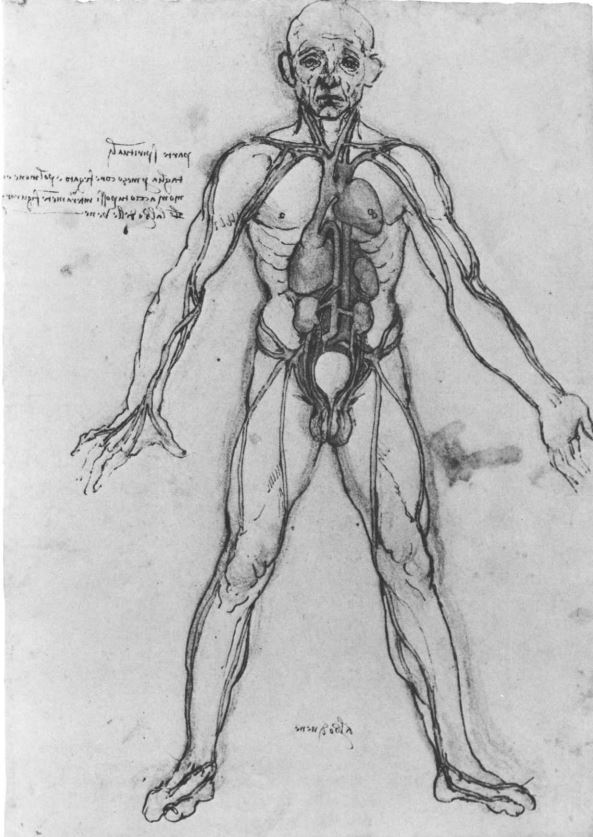

Da Vinci’s Sketch of the Human Organ System

One way in which Da Vinci was unique was his pioneering of the research field in human anatomy. Because 15th century anatomy books offered very little practical knowledge, he relied mainly on his own experiments and observations. He was one of the first people to dissect human bodies, even without any professional training. The illustrations of his cadavers were critical for understanding and improving medical research both ex-vivo and in-vivo.

An area of Da Vinci’s anatomical fascinations involved the inner organs. By combining anatomy with physiology, he was able to identify simple and complicated mechanics that engineered the human body. He demonstrated that there existed hidden layers that separated the different organs through dotted lines within individual illustrations. He applied perspective and mark-making from his art concentration to communicate his incredible depictions of human proportions.

Interestingly, he believed that the human body and the universe were aligned. In his image, human body parts were analogous to the composition of the planet. This urge for finding connections in different subjects was representative of Da Vinci’s hunger for knowledge.

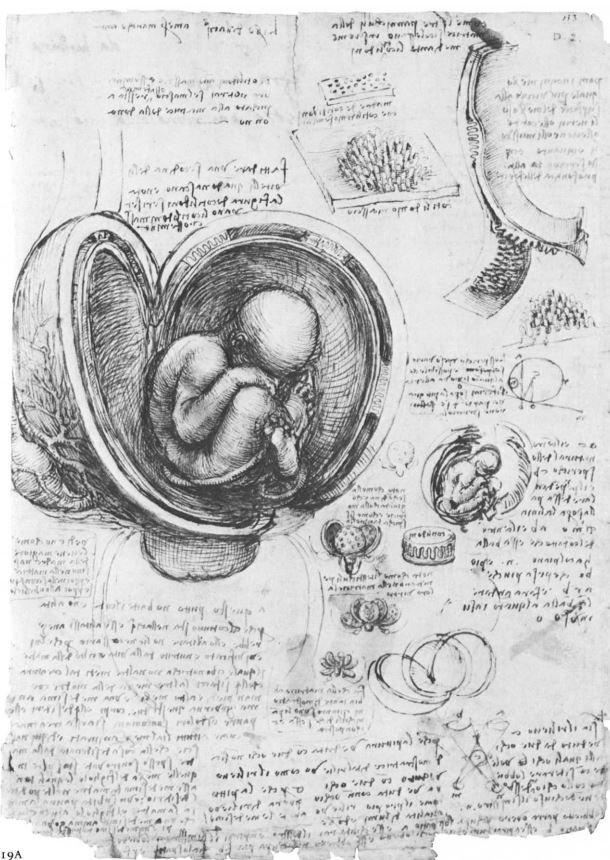

Leonardo da Vinci’s Depiction of a Fetus in the Womb

Another anatomical feat of his was Da Vinci’s accurate reconstruction of a fetus inside the womb. He was the first to correctly illustrate a human fetus inside of the mother’s womb without the need for a real cadaver. Instead, the polymath’s use of a previous cow dissection to recreate the scene is a testament to his creativity towards scientific applications.

Overall, Leonardo da Vinci is a perfect representation of this website’s purpose: to unify art and science as a single concentration. Da Vinci’s creativity, perseverance, and technical skill have placed him among the top artists and scientists of history. Once again, this blog is simply the tip of the iceberg with most of his life details—such as the intricacies of the painting process for the Mona Lisa or the Codex Arundel—being unmentioned. However, his notebooks and written works can be accessed through online archives and public domains which I strongly encourage you to explore.

h

References

Dennison, B. (2017, May 1). Leonardo da Vinci’s scientific visualizations: “Saper verdere” or knowing how to see | Blog | Integration and Application Network. Ian.umces.edu. https://ian.umces.edu/blog/leonardo-da-vincis-scientific-visualizations-saper-verdere-or-knowing-how-to-see/

Hetisimer, C. (2019, May 6). Da Vinci’s Fetal Studies. Editions.covecollective.org. https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/da-vincis-fetal-studies#:~:text=Da%20Vinci%20was%20the%20first%20to%20correctly%20draw

History.com Editors. (2009, December 2). Leonardo Da Vinci. History.com; A&E Television Networks. https://www.history.com/topics/renaissance/leonardo-da-vinci

Keele, K., Pedretti, C., & Roberts, J. (1977). Leonardo Da Vinci. Royal Library, Windsor Castle.